Summary: The neoclassical economics, assumptions, methods and data used by William Nordhaus and other economists in their models (known as IAMs, Integrated Assessment Models), on how the economy interacts with climate change, are flawed. They rely on narrowly defined data, projected into the future in simplistic ways, that grossly underestimates the likely impacts of global warming on the economy, and in broader terms. These misrepresentations have acted as a fig leaf that have enabled policy-makers and politicians to avoid taking urgent action to reduce carbon emissions, and has therefore already done incalculable harm. It is not too late to base policies on scientifically grounded estimates of future impacts, and to ensure these deliver a fair transition to a net zero future.

A fundamental question

A fundamental questions is how much warming can we realistically tolerate to avoid serious damage? As we will see, economists have hitherto come up with surprisingly high estimates in answer to this question.

I know I am not alone in being both puzzled and angry at the apparent lack of urgency shown by governments to the growing risks of man-made global warming. For the purposes of this essay, let us be generous and assume that these politicians aren’t from the breed of economic liberals who obdurately denigrate climate science for ideological reasons.

We are nonetheless left with something far more insidious and dangerous. Mainstream policy-makers and politicians who walk the corridors of Westminster and other centres of power who seem quite happy to see new fossil fuel exploration, and keep putting off urgent plans to transition to a net zero future. They fail to acknowledge that not all paths to net zero are the same [1].

So what is going on?

Nordhaus’s neoclassical economics

One explanation for this lack of urgency is because economists hold much more sway with policy-makers than scientists, and hitherto, economists have been telling a quite different story to the one we hear from scientists.

Scientists will say that an average rise in global mean surface temperatures of 4°C or more over a mere century or so would be catastrophic. Scientists will point out that the PETM (Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum) 56 million years ago was estimated as being a rise of about 5°C (which occurred over a period of several thousand years) [2].

While we do see temperature ranges between the tropics and polar regions that greatly exceed 5°C, it is a misunderstanding (that infects the work of some economists) to imagine that this should be a source of comfort. Heating the whole world by 5°C is an enormous amount of energy that has in the past and would in the future knock the climate into a completely new state. It would be an end to the relatively stable climate in which humanity and nature has co-evolved and co-existed, and do this not in several thousand years but in a mere century. A blink of the eye.

Yet William Nordhaus, whose pioneering work on IAMs won him the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2018, estimates economic damages by the middle of the next century to be just 2.1% with a warming of 3°C and 8.5% with a warming of 6°C [3]. Bear in mind that 8.5% drop on GDP is less than two times the financial crash following the 2008 banking crisis (about 6% drop for the UK).

So, during a global temperature rise that will bring mass extinctions, hugely destructive sea level rise, etc. Nordhaus’s economics seems to just give a shrug! Nothing to see here. Any wonder then that Rishi Sunak is also giving a shrug, and why the UK Treasury and many other arms of Government seem not only relaxed about climate change but in many cases have, and continue, to actively frustrate the path to net zero.

I should add that Nordhaus himself adds words of warning [3]:

“Because the studies generally included only a subset of all potential impacts, we added an adjustment of 25 percent of quantified damages for omitted sectors and nonmarket and catastrophic damages …”

So, there’s a whole lot we don’t know or are not measured well enough, so let’s add a measly 25% to the narrowly circumscribed and quantifiable impacts. Wow! Why not 250%, or 500%?

Other economists have been deeply critical of this approach and regarding specific aspects of the modelling. Issues include:

- the scope of impacts included is quite narrow. A key reference used by Nordhaus acknowledges “As a final conclusion, we emphasize the limited nature of work on impacts.” but that does not seem to stop them publishing [4]

- many often questionable parameters are included. For example, extrapolating from current meagre efforts to date “it is assumed that the rate of decarbonization going forward is −1.5 percent per year” [3], yet detailed analysis of existing technology indicates dramatic worldwide savings totalling trillions of dollars by 2030 are achievable with ambitious decarbonisation policies and plans [5].

- using the productivity of different regions with current climatic variability, such as the continental USA, as a way to calibrate forward in time, over many decades, the impact of global warming, signals a complete misunderstanding of climate change and is grossly misleading.

- discounting damages is based on current data for goods, so grossly underestimates impacts on future generations (the Stern Review had a lot to say about discount rates).

- extrapolations from current data is done using simple smooth functions, whereas we can expect discontinuities and abrupt changes as the world warms, in thousands of systems in a myriad of ways (more to say on this below in thresholds and system impacts)

The UNFCCC (UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) originally set the target for peak global warming to be 2°C, with a supplementary Paris Accord ambition to keep it to 1.5°C, under pressure from the most vulnerable nations. Yet the current policy commitments (the Nationally Determined Contributions) from the parties to the convention would take us currently to between 2.6°C and 4°C according to the UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2022 [6].

A critique of neoclassical economics

Steve Keen has provided a comprehensive and excoriating critique of the work of Nordhaus and others in his paper The appallingly bad neoclassical economics of climate change [7]. I want to pull out a few key observations (quoted snippets) from Keen’s paper, but please study the paper in full:

- Nordhaus excludes 87% of US industry from consideration, on the basis that it takes place ‘in carefully controlled environments that will not be directly affected by climate change’

- Nordhaus’s list of industries that he simply assumed would be negligibly impacted by climate change is so broad, and so large, that it is obvious that what he meant by ‘not be directly affected by climate change’ is anything that takes place indoors – or, indeed, underground, since he includes mining as one of the unaffected sectors (more to say on this below in thresholds and system impacts).

- If you then assume that this same relationship between GDP and temperature will apply as global temperatures rise with Global Warming, you will conclude that Global Warming will have a trivial impact on global GDP. Your assumption is your conclusion.

- Given this extreme divergence of opinion between economists and scientists, one might imagine that Nordhaus’s next survey would examine the reasons for it. In fact, the opposite applied: his methodology excluded non-economists entirely.

- There is thus no empirical or scientific justification for choosing a quadratic to represent damages from climate change – the opposite in fact applies. Regardless, this is the function that Nordhaus ultimately adopted.

- As with the decision to exclude ∼90% of GDP from damages from climate change, Tol’s assumed equivalence of weather changes across space with climate change over time ignores the role of energy in causing climate change.

- What Mohaddes called ‘rare disaster events’ – such as, for example, the complete disappearance of the Arctic Ice sheet during summer – would indeed be rare at our current global temperature. But they become certainties as the temperature rises another 3°C.

- The numerical estimates to which they fitted their inappropriate models are, as shown here, utterly unrelated to the phenomenon of global warming. Even an appropriate model of the relationship between climate change and GDP would return garbage predictions if it were calibrated on ‘data’ like this.

Deeply problematic, as Keen points out:

The impact of these economists goes beyond merely advising governments, to actually writing the economic components of the formal reports by the IPCC (‘Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change’)

and he concludes:

That work this bad has been done, and been taken seriously, is therefore not merely an intellectual travesty like the Sokal hoax. If climate change does lead to the catastrophic outcomes that some scientists now openly contemplate … then these Neoclassical economists will be complicit in causing the greatest crisis, not merely in the history of capitalism, but potentially in the history of life on Earth.

Beyond Nordhaus

It seems that Nordhaus and others have been able to pursue their approach because they had free rein for too long in what seemed to be a relatively niche field (when compared with the majority of climate change related research). It would be easy to shrug concerns off as a squabble amongst academics in an immature field of research.

Wrong! The issues are not of mere academic interest but have real-world consequences for policies and climate actions being undertaken (or rather, not undertaken) by governments and industry. For example, a recent paper by Rennert et al [7] on the social cost (SC) of carbon dioxide (CO₂) notes:

For more than a decade, the US government has used the SC-CO2 to measure the benefits of reducing carbon dioxide emissions in its required regulatory analysis of more than 60 finalized, economically significant regulations, including standards for appliance energy efficiency and vehicle and power plant emissions.

and this paper arrives at a social cost for carbon dioxide that is 3.6 times greater (that is 360% higher) than the value currently used by the US Government, and leads to their conclusion that:

Our higher SC-CO2 values, compared with estimates currently used in policy evaluation, substantially increase the estimated benefits of greenhouse gas mitigation and thereby increase the expected net benefits of more stringent climate policies.

In plain English: we urgently need to stop burning fossil fuels.

Other papers are now amending IAMs to be more realistic. One paper titled Persistent inequality in economically optimal climate policies [8] notes:

The re-calibrated models have shown that the Paris agreement targets might be economically optimal under standard benefit-cost analysis.

These researches are however concerned at the narrow cost-benefit global approach. They take a more detailed look at the differences between and within countries when it comes to the fairness of future pathways. They find that the economic response to climate change will vary greatly depending on the level of cooperation between countries. The conclusions are curiously both optimistic and depressing:

Results indicate that without international cooperation, global temperature rises, though less than in commonly-used reference scenarios. Cooperation stabilizes temperature within the Paris goals (1.80°C [1.53°C–2.31°C] in 2100). Nevertheless, economic inequality persists: the ratio between top and bottom income deciles is 117% higher than without climate change impacts, even for economically optimal pathways.

So better modelling indicates we can dial back on the ludicrous Nordhaus ‘optimal’ warming estimates to something closer to the UNFCCC’s 2°C, as a target that policy-makers and politicians should take seriously. The bad news is that the well known deep inequalities that exist in how climate change plays out will not be remedied merely by staying within the 2°C limit.

Other things must happen – in the solutions that are adopted and how these are implemented within countries and across regions – to ensure that inequalities are not perpetuated or even widened.

Thresholds and system impacts – nature

I want to illustrate the idiocy of the approach taken by Nordhaus and others who use IAMs to project implausibly minimal impacts resulting from 3°C to 6°C of global warming.

It speaks not merely to the lack of an appreciation of how systems work in the real world, but also, a complete absence of imagination.

Systems thinking has recently become a buzz word in some UK Government departments, but it is not obviously reaching the parts of the Treasury or Number 10 Downing Street where decisions are made.

We don’t need one of the much talked about major tipping points (e.g. loss of Arctic Sea Ice) to suffer extremely severe consequences from global heating.

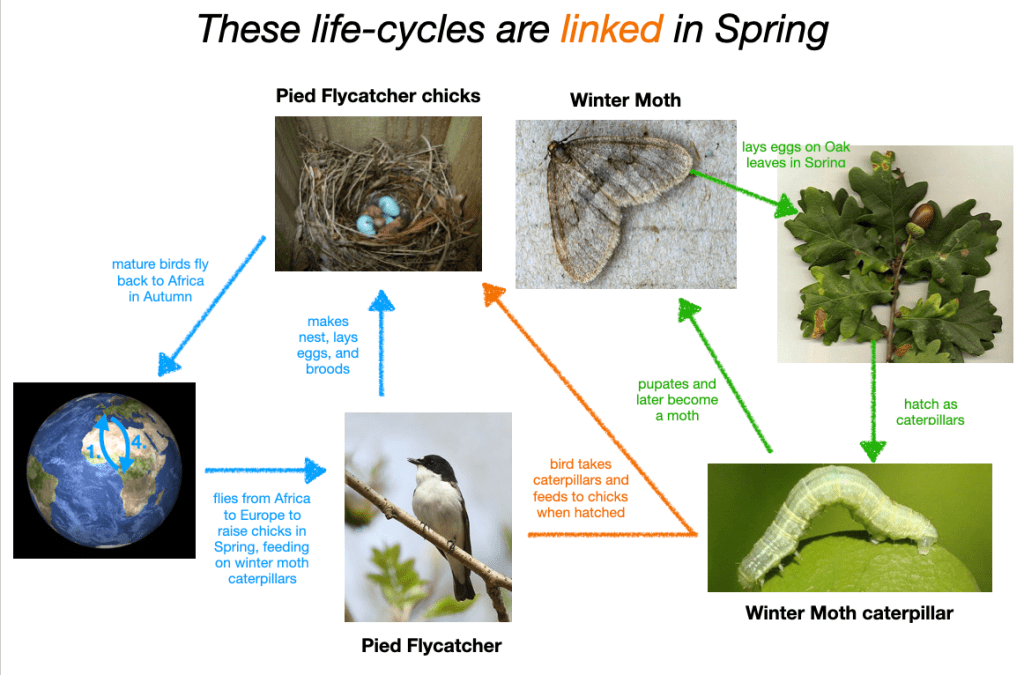

When talking to young people about climate change there is a story I like to tell that helps illustrate how a small change in global mean surface temperature can have a big impact, and it concerns the Pied Flycatcher. This is a picture I created when talking to Primary School children (picture me also holding a globe at the same time to show the migratory paths).

This what I say:

“The Pied Flycatcher flies from Africa to northern Europe just in time to nest so it can feed its hatchlings on the caterpillars of the Winter Moth, which in turn feed on the leaves of oak trees.

But the oak trees have been coming into leaf a few weeks earlier, due to global warming, and the moths have adapted.

But the Pied Flycatcher in Africa is unaware of this, so it arrives at its normal time of the year only to find that caterpillars to feed its hatchlings are scarce.

Fewer hatchlings survive to make the return journey to Africa later in the season, so their numbers decrease.

This has all happened owing to only a small change in the temprature, because life-cycles of the bird and moth that worked together have now being disrupted.“

It is not hard to see that the link (the red arrow) between these separate life-cycles has been broken and has thereby disrupted the system as a whole. There has been a severe decline in their numbers as a result of this ecological dislocation [9], and this (at the time) with less than 1°C of global warming.

In general, nature can adapt to changing climate, but within limits and only at certain ‘speeds’. A species of plant that likes cold conditions might migrate further up a mountain as the climate warms, but eventually it will run out of mountain!

With global warming now being so fast, nature cannot fully adapt or evolve to the changes being wrought.

Thousands of such ecological (and indeed physical and societal) thresholds have been crossed and will be crossed.

Thresholds and system impacts – human society

Let’s move to another example of how climate change is already having an impact – and in this case with industry.

Last summer there was a drought in Europe. Politico reported [10]

Water levels on the Rhine, Europe’s major inland river connecting mega-ports at Rotterdam and Antwerp to Germany’s industrial heartland and landlocked Switzerland, are precipitously low …

That’s a pressing problem for major industries, but it also puts a damper on EU plans to increase the movement of goods along waterways by 25 percent by 2030 and by 50 percent by 2050 …

So those factories that are ignored by Nordhaus because they are indoors find that their raw materials struggle to get in and their produce struggles to get out, when the Rhine is dried up. Not exactly rocket science insight! Note here the complex picture of potential harmful feedbacks:

- global warming causes an extreme weather event (a widespread drought)

- the drought causes low waters in the Rhine

- the low water in the Rhine adversely impacts the passage of material and thereby the manufacturing sector

- mitigation steps would require more land transport, leading to greater net emissions (but could not completely replace the tonnage provided by shipping)

- greater net emissions increase the risk of extreme weather events.

It really isn’t hard for even young children to work this out (I’ve had conversations along these lines with 12 year olds) but apparently too hard for some economists.

One of economist (surveyed by Nordhaus), Larry Summers, replying to one question said ’For my answer, the existence value [of species] is irrelevant – I don’t care about ants except for drugs’. I guess no one has told him that insects pollinate plants and are therefore an essential part of life on Earth, including human life, and hence our economy. It starkly illustrates the recklessly narrow scope of climate impacts considered by some economists.

Conclusion

For too long, policy-makers and politicians, in the UK, USA and elsewhere have been able to justify their inaction on climate because of the economists like William Nordhaus telling them that a warming globe will have essentially only marginal impacts on the economy. A 2015 survey of the social cost of carbon used by countries [11] found a number of countries using an average 2014 price of $56/tCO2 similar to the USA (rising to $115 in 2050). The UK is actively reviewing how it puts a cost on carbon, as in a January 2023 paper by the BEIS Department [12].

Nordhaus would now say that he is calling for early mitigation, at least on a precautionary basis, but that is a bit like calling the fire brigade when the fire is already well established.

It is time for policy and action to be based on science, systems thinking, and a just transition, rather than some approaches and models that are well past their sell-by date.

George Box quipped that ‘All Models are wrong but some are useful’.

In the form that William Nordhaus and others have developed IAMs over the last few decades, a better aphorism to use might be:

‘All models are wrong, and some are dangerously misleading’.

Thankfully, if belatedly, other economists have been teaming with climate scientists, and challenging and improving the models. Models are needed, and can be useful, to guide our thinking. There is still much work to do. We need to be able to ask ‘what if …?’ type questions to see what the future might look like with different assumptions, and drive ambitious policies.

It’s now time for policy-makers and politicians to recognise the need to radically review their policies and actions, based on the best available approaches and models.

(c) Richard W. Erskine, 2023

References

- Not all paths to net zero are the same, Nailsworth Climate Action Network, 5th October 2023, https://www.nailsworthcan.org/blog/not-all-paths-to-net-zero-are-equal

- Is 2°C a big deal?, https://essaysconcerning.com/2021/10/14/is-2c-a-big-deal/ (including references to specific sections of the IPCC AR6 Report).

- Nordhaus, W. Projections and Uncertainties about Climate Change in an Era of Minimal Climate Policies. 2016 Am. Economic J. 10, 333–360, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.20170046

- Nordhaus, William D., and Andrew Moffat, 2017 A Survey of Global Impacts of Climate Change: Replication, Survey Methods, and a Statistical Analysis, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper 23646, https://www.nber.org/papers/w23646

- Decarbonising the energy system by 2050 could save trillions – Oxford study, Oxford University, https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2022-09-14-decarbonising-energy-system-2050-could-save-trillions-oxford-study

- UNEP Emissions Gap Report, 2022, https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2022

- K. Rennert et al, 2022, Nature, 610, 687–692, Comprehensive evidence implies a higher social cost of CO2, DOI 10.1038/s41586-022-05224-9, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-05224-9

- Gazzotti, P. et al. Persistent inequality in economically optimal climate policies. 2021 Nature Communications 12, 3421 (2021). DOI 10.1038/s41467-021-23613-y. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-23613-y#citeas

- Both, C., Visser, M. 2001 Adjustment to climate change is constrained by arrival date in a long-distance migrant bird. Nature 411, 296–298 (2001). DOI 10.1038/35077063. https://www.nature.com/articles/35077063#citeas

- Joshua Posaner and Hanne Cokelaere, Deep trouble for EU shipping push as Rhine River runs dry, Politico, 7th August 2022. https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-rhine-river-climate-change-heath-shallow-rhine-undermines-europes-waterways-push/

- Smith, S. and N. Braathen, 2015 Monetary Carbon Values in Policy Appraisal: An Overview of Current Practice and Key Issues”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 92, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jrs8st3ngvh-en.

- Valuation of energy use and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions: Supplementary guidance to the HM Treasury Green Book on Appraisal and Evaluation in Central Government, January 2023, Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

Extraordinarily well-written and to the point. Thanks.

My big-picture take is that humans have fundamental flaws that make us incapable of understanding what we’ve done — and are doing. Those flaws might ensure our demise.

1. Scale: We can barely imagine a time greater than a lifespan, yet the changes we’ve made have happened in a geologic blip in time. On the other hand, the amount of energy our actions have added to the oceans and atmosphere is incomprehensible.

2. Change: Everyone alive has lived through massive changes and become complacent about change. We view change as progress, but sometimes it is exactly the opposite and is actually existential.

3. Comfort: We seek comfort. The bubbles we live in are comfortable but have enormous costs that will be paid by future generations. We will do almost anything to remain comfortable.

4. Growth: We assume infinite growth, more, more, more. On the face of it, this is absurd.

5. Fixes: We make problems, but we fix them really well. We assume we can fix anything, but there are limits. Because of the massive changes we have made in such a tiny period of time, there’s an extremely good chance that the problems are well beyond our capability to fix.

There are many more fundamental human flaws (evolutionary baggage), but these are the ones that come to mind at this moment.

While I realize it sounds defeatist, I simply cannot see how we get out of this mess. The simple fact that we could have used the massive amount of energy we extracted from the Earth over the past couple of hundred years to make everyone happy but didn’t is evidence enough for me. During that same period, science and engineering gave us extraordinary knowledge and tools. Instead of making humanity and the planet better, we messed it up. We blew our chance.

I only have a single hope for humanity and the planet: that something smarter than us will find a way to fix the mess we’ve made.

LikeLike

Thank you Will for your comments – sorry for the delay is replying. I agree the challenge is massive. My belief is that there will be societal tipping points that will force Governments to act. Even in the USA, this can happen because the majority want it – and states will make it happen even if the GOP get back in and try to prevent it at Federal level. In the UK, when pension funds stop putting money into fossil fuels, that will be another shift. The transition will be messy and with many back and forths. The result will be a world’s climate far more disrupted than it could have been with better leaders (and better citizens?); but not as bad as is could of been if we hadn’t acted, albeit belatedly.

LikeLike