This post is a section / extract from my book Trusted Knowledge in a digital and fragmented world of work which is available as a hardback, paperback or e-book on Amazon. Several of the previous sections in the book provide the underlying know-how on how to deal with difficult areas such as access to sensitive information. I believe that the book has relevance to all sectors but given the UK Government’s call for a national conversation in its aims towards Creating a new 10-Year Health Plan. Here follows the section Healthcare’s Knowledge Architecture, including (with her permission) the treatment pathway of my wife’s successful treatment for breast cancer from 25 years ago at Cheltenham General Hospital, starting with a description of key principles ...

I want to focus on the question of knowledge as it is shared within a healthcare system, as an exemplar of the opportunities to improve information and knowledge management. If we look at the regular clinical experience of patients within the healthcare system of the UK, with a National Health Service (NHS), one might expect that someone on holiday taken ill could walk into any hospital at the other end of the country, and the clinicians would be able to immediately access information needed to assess a patient. This is not the case, despite many years of trying to fulfil this outcome, and billions spent on IT, including the disastrous National Program for IT (NPfIT) failure.

Fragmentation of data and systems exists in many countries for a variety of reasons. In the USA, it is down to the privatised, metric driven, insurance funded fiefdoms which dominate the sector. Some countries, such as Finland, have managed to crack the problem, but this is an exception, not the rule.

Healthcare is a sector that is a great exemplar for both the challenges and opportunities of improved information and knowledge management, and I wanted to use it as a vehicle for illustrating several of the key principles that have been central to this book.

IT delivery across healthcare has been marked by a highly fragmented approach. Many healthcare organisations find that they have accumulated several hundred systems, creating a large number of data and document silos. Often, because there are not the funds to do a proper fix, another ‘bolt on’ remedy will be implemented.

While this has caused operational issues, it has fundamentally hampered the ability of clinicians to have a unified view of a patient or patient pathway, and this can have a significant impact on the quality of patient care.

Even when a basic unified medical record has been achieved, much of the associated data has remained inaccessible, and there is still an over reliance on paper or on relatively primitive digital approaches to ‘unstructured’ data, which has remained stubbornly siloed. In many practices it is not a lack of IT solutions that is the issue, but a fragmented approach that has led to a lack of joined up data and information, let alone knowledge.

In the section The Data Landscape, I discussed how transactional systems have tended to get the most attention and funding in organisations, whereas the more ‘knowledge oriented’ processes and systems are often neglected. This is also true in healthcare, but fragmentation has been common for all types of systems, particularly in cash-strapped hospitals; they have fallen back on a cottage industry approach to IT systems that has further fragmented the delivery of solutions.

This is not to advocate a top-down approach to systems. In the NHS this was tried and singularly failed because it imposed a rigid approach in areas where there should arguably be more freedom (such as in the procurement of software).

It could instead have had a more fundamental and achievable goal, to create standards (such as an information architecture) that facilitated data and information sharing, without being prescriptive on solutions delivery. What would a process look like that delivered such standardization to the NHS?

I want here to sketch out some aspects of the methodology that is outlined in this book, and I am interested in focusing the exposition on the ‘patient pathway’. The analysis starts with the identification of Essential Business Entities (EBEs); those entities that would exist however the management decided to reorganise or despite several generations of systems. For healthcare, the following are an incomplete list of EBEs:

- Admission

- Appointment

- Clinic

- Clinical/Medical Image

- Clinical Pathway

- Consultant

- Consultation

- Discharge

- Doctor

- General Practitioner

- Examination

- Healthcare Provider

- Hospital / Clinic

- Investigative Procedure

- Laboratory Test

- Medical Record

- Medical Specialist

- Medication

- Nurse

- Observation

- Patient

- Payer

- Pharmacy

- Prescription

- Regulator

- Referral

- Report

- Treatment

For some EBEs, such as ‘Regulator’, there is no work related to it from the organisation’s perspective (because it is a pre-existing entity and not something that requires anything from the healthcare provider to create or manage it). For this reason, we are only interested in EBEs that generate work within the scope of the organisation (e.g. within a healthcare provider).

In addition, because we want to analyse patient pathways, the focus is on those EBEs that are most relevant in the current context, such as: Referral, Observation; Patient; etc. The Process Architecture below reflects this focus.

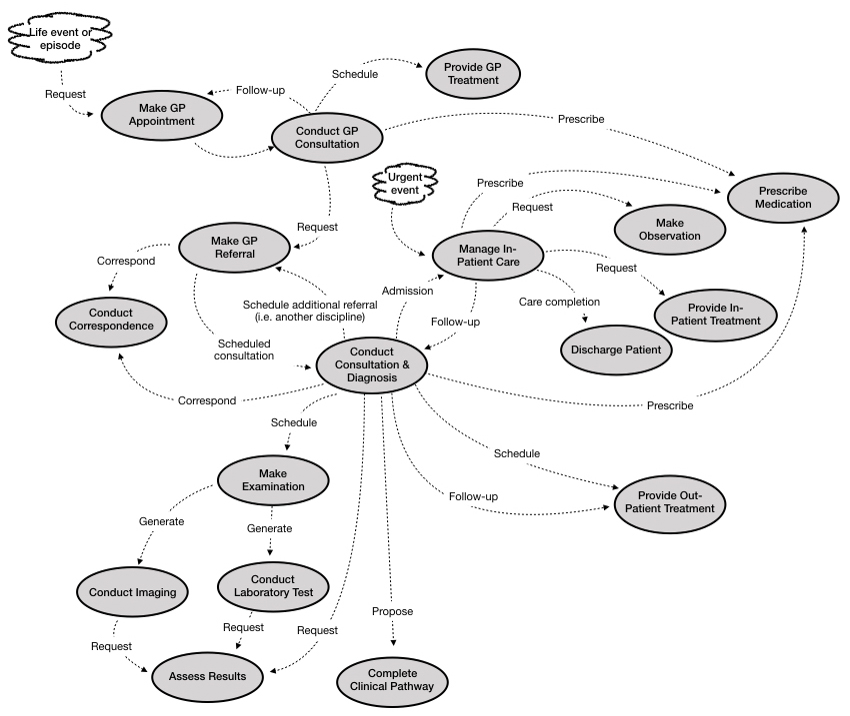

Figure – Patient Pathway Process Architecture

The aim of a process architecture is to indicate how each process ‘invokes’ possible subsequent processes; this is not a dataflow, or workflow, but a graph showing the possible sequence of invocations.

On a patient pathway such as cancer treatment and after-care, a particular process such as Make Examination can be invoked many times over several years, as the patient passes through the different interlocking cycles of referral, examination and treatment.

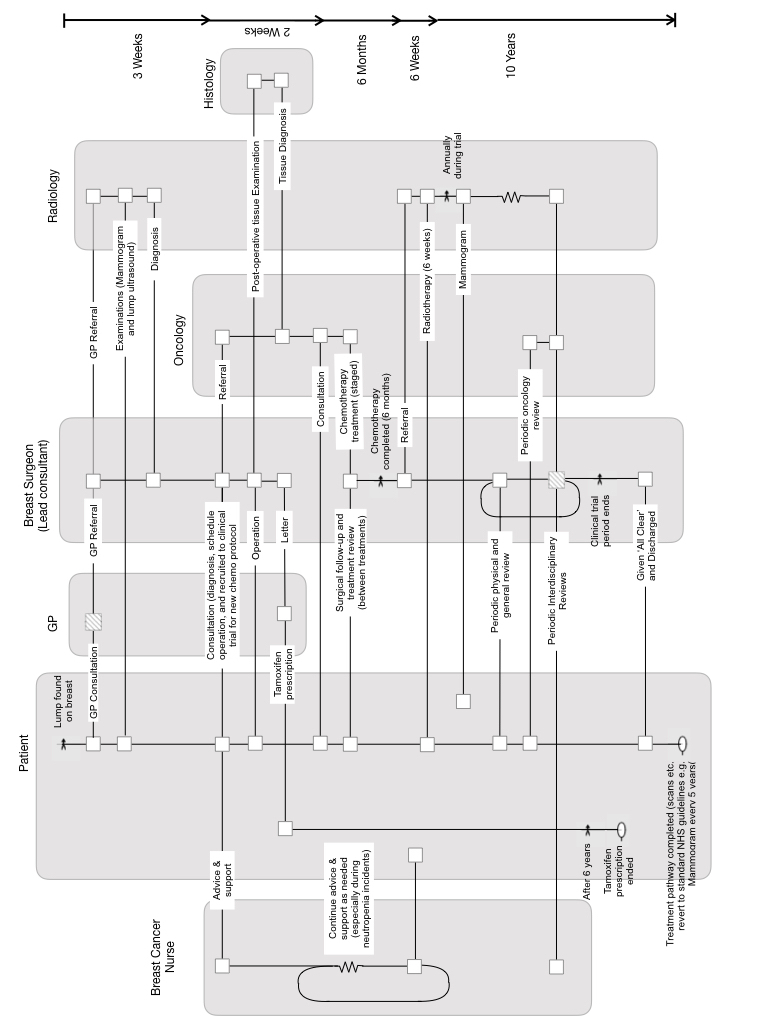

My wife (who I thank for giving permission to share her story) was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1999, soon after we had moved house. It was a terrible shock to the whole family. We visited the senior breast cancer consultant at Cheltenham Hospital and recall being the last to see him, late on a Friday afternoon. He sat with my wife and I for over an hour, and never once looked at his watch. He explained the options clearly. He calmed us down. The path ahead would be difficult but we could make it. He gave us the confidence we needed. I had read that the key to successful cancer care was not necessarily the things we imagine – the specific drugs used and other technicalities – but the communications and particularly the team-work amongst the healthcare professionals.

Luckily for us, Mr. Bristol and the team at Cheltenham were exceptional. I know that there were occasions when how I acted, as part of the extended team, would be critical. For example, when my wife became drowsy and I knew from my briefings from the Breast Cancer Nurse that I needed to be alert to the possibility of low white cell count; and that a possible dash to the hospital and isolation ward might be called for. This happened twice during the chemotherapy, and we are forever grateful for the knowledge that the nurse instilled in us.

The usual process with chemotherapy for breast cancer was to use the milder drug first and only use the harsher drug for subsequent treatment. My wife agreed to take part in a clinical trial for a new protocol where these treatments were reversed; there would be a hard hit first, followed by a longer sequence with the milder drug.

The involvement in the trial meant that my wife was monitored and assessed long after most patients would have been fully discharged by the hospital – even those who had moved onto a post-chemo hormone suppressant treatment, such as Tamoxifen. In my wife’s case, she was only fully discharged after 10 years, and while the trial was completed some time ago, the data from her case continues to inform scientific research on Breast Cancer, more than 20 years after she was diagnosed.

In the summer of 2019, she received a request to access samples of tissue, held in storage, as part of continuing research; the documentary records themselves will be equally valuable for current and future research.

Figure – The Long Pathway of a Breast Cancer Patient

Protecting personal confidentiality is important, which is why some records need to be transferred in a way that does not identify the patient; this is preferrable to simply deleting records after arbitrary retention periods. This would limit the ability to carry out longitudinal studies, and assess the efficacy of treatments over long periods.

The duration of this pathway is very long compared to the waves of change that occur in IT. This emphasises the need for an approach to information management and the handling of records that is resilient to these changes, to minimise or even eliminate the need to transcribe and convert data and documents between systems on ever shorter cycles.

At the heart of the approach to handling this change, is the ‘Electronic Health Record’ (EHR) – which is usually conceived of as the complete history of an individual’s clinical encounters: examinations, diagnoses, treatments – so perhaps better thought of as a dossier of health records. It is essentially the digital equivalent of the manilla file that a General Practitioner would previously retain in your local surgery (at least in the UK), including correspondence with specialists and hospitals, referred to during treatments that could not be dealt with locally. Now, however, the EHR is seen as including literally everything including, for example, the digital X-ray files created during an examination.

The idea of a single system being responsible for all aspects of a person’s clinical pathway is not realistic: there are specialist, dedicated systems for MRI (Magnetic-Resonance Imaging), and each discipline. What is possible is that each system such as this can share the records it generates on a secure network, and some central repository can add each record into a patient ‘dossier’ without interfering with the source system.

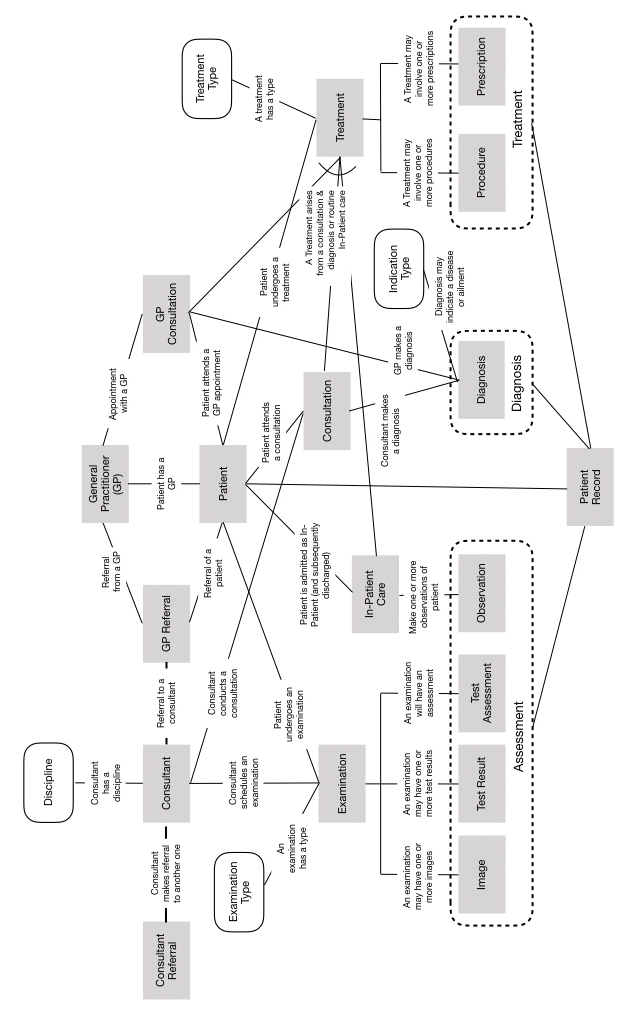

Figure – Conceptual Information Model

The dossier itself could be stored, and if necessary moved, in a non-proprietary form, such as XML using a standard structure applicable to health records. This can be modelled conceptually as in a Conceptual Information Model, as depicted above.

An individual’s health record will grow and grow, and in addition to the pathway discussed above will include interventions small and large – the cut on the knee, the treatment for a skin condition, and so on and so forth – from birth to death. So how would a health professional interact with this information?

It must be possible to filter and segment access according to the role of the health professional. A technician who is undertaking an X-ray does not need full access to the whole health record, whereas a general practitioner does. If it is a team meeting to discuss next steps for a cancer patient, then they all need to see the diagnosis, treatments and observations made by all professionals who have been part of the treatment pathway. They might interact with the information through a timeline view of the information, that could reveal something like the long pathway shown earlier, but allow them to zoom in and out of the timeline, and move back and forth in time.

To make this as much a knowledge platform as a data and information one, they need the ability to add notes and annotations to this timeline, to make sense of decisions made, and perhaps course changes made on the pathway. The pathway would reference the current protocols and standards being used, but also, in the case of an innovative trial, the basis for the decisions being made.

Quite separate from the particularities of one patient, work is done to manage and maintain those protocols and standards. There will be the development of new protocols based on evidence from published research as well as on local knowledge of the team, or health trust, or at a national level. It is a continual process or review and challenge. In the UK, we have the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), whose job is to evaluate the efficacy of drugs and treatments, based on the shared national experience. NICE also will assess the relative benefits of one treatment compared to another in terms of health outcomes as a function of costs. This sounds as if it could be a difficult role, and it is, but the NHS does not have an infinite budget, and so if a treatment will extend life by 3 years and costs £50 a week, and another that will extend it for 5 years but costs £1000 a week, there is a utilitarian argument that says that for 10,000 people needing treatment, the first treatment is actually more cost effective, and if budgets are capped, will deliver more years of life extension.

A body like NICE is powerful, because it is often difficult for one professional or even a healthcare unit, to have the breadth of experiences required to evaluate options, even with access to the published literature. Local knowledge sharing is crucial, but it should not be an excuse for an insular approach. The knowledge must flow laterally, between professionals, and vertically, to inform regional and national good practices.

Specific disciplines will have their own knowledge repositories that provide the commentary, stories and narrative that are essential in making sense of the hard numbers, or received wisdom. The radiologists who discuss their methods and approaches, and how they collaborate with other specialists, will contribute to the performance of the diverse teams, such as in cancer care.

Genomics data linked to health records for ‘big data analytics’ – and machine learning to find patterns in that data – will make increasingly large impacts on the choice of treatment protocols. However, as I have argued earlier, this must be seen as a tool that supports the collective knowledge of teams and disciplines. Humans can contextualise knowledge arrived at from personal experience, drug trials or big data. Only humans can summarise that knowledge in a way that combines science, ethics and the wishes of individual patients and families.

Ultimately, health professionals must make choices on treatment pathways, and it is they who must collectively curate a body of knowledge that makes sense of data and information and how to apply that knowledge in a specific context.

A fully developed architecture of knowledge – that respects the principles and practices outlined in this book – is therefore an essential feature of any healthcare system, where knowledge sharing and learning are valued.

Trusted knowledge is crucial to any organisation – working in healthcare or any other sector we might wish to explore – and I hope that this book will make a significant contribution to its advancement.

(c) Richard W. Erskine, 2024