I was excited to get my hands on Jean-Baptiste Fressoz’s latest book More and More and More – An All-Consuming History of Energy [1]. He offers up a very lively critique of the notion of historic energy transitions – from wood, to coal, to oil and gas.

His methodology aims to show how material flows are intimately linked to energy production in often surprising ways over time. For example we needed wood as pit props to mine coal, and in surprising quantities. Most of the book is devoted to examples of the symbiosis that has existed between the successive materials required to meet our energy needs. He mocks the idea of energy transitions with numerous well researched anecdotes, awash with surprising numbers. It is an entertaining read I would recommend to anyone.

However, I was expecting the book would close with some prescriptions that would show how the “amputation” the blurb called for could be achieved, but in the end he tells us he offers no solutions, or “green utopias”, as he discussed in an interview [2].

In the finale, he presents the newest energy transition – towards a world powered by renewables – as just the latest incarnation of a delusional concept, but largely abandons his methodology of using numbers to prove his case. I wonder why?

He does not deny the reality of a need to reduce carbon emissions, or the science of climate change, but it is clear he sees humanity’s insatiable appetite for energy as the central issue that must be addressed. He could have written a different book if that was his objective.

There are fundamental flaws in Fressoz’s scepticism of the renewables transition.

Solar abundance

The first of these is that the new source of energy that supplies our energy in a renewables future is our sun. Energy from the sun is a quite different category to that we extract from the ground.

The most pessimistic projection is that humanity, or what we may become, will have hundreds of millions of years left of usable energy from the sun [3]. No digging or extraction required. I’d call it functionally infinite on any meaningful timescale.

Not only that, but the sheer power of the sun’s energy is awesome, which we capture as wind, through photovoltaics, and the ambient energy harvested by heat pumps. As Frank Niele observed 20 years ago [4]:

“The planet’s global intercept of solar radiation amounts to roughly 170,000 TeraWatt [TW] ( 1 TW = 1000 GW). … [man’s] energy flow is about 14 TW, of which fossil fuels constitute approximately 80 percent. Future projects indicate a possible tripling of the total energy demand by 2050, would correspond to an anthropogenic energy flow of around 40 TW. Of course, based on Earth’s solar energy budget such a figure hardly catches the eye …”

It is clearly a category error to compare renewables with fossil fuels.

False equivalence

Ah, but what about the lithium and all those (scare story alert) “rare earths” needed to build the renewables infrastructure. This is the second flaw in the Fressoz thesis. The example of wood consumption for mining staying high even after the ‘transition’ to coal, is an example of an essential material relationship between the kilowatt-hours of energy produced and the kilograms of material consumed. This link does not exist with renewables to any meaningful degree.

It has nevertheless become a popular belief amongst those questioning the feasibility of renewables. For example, Justin Webb on BBC Radio 4 [5] posed this question:

“Is it also the case of us of us thinking whether we can find some other way of powering ourselves in the future … [we are] just going from taking one out of the ground – oil – into taking another thing or another set of things just isn’t the answer, isn’t the long-term answer for the planet.”

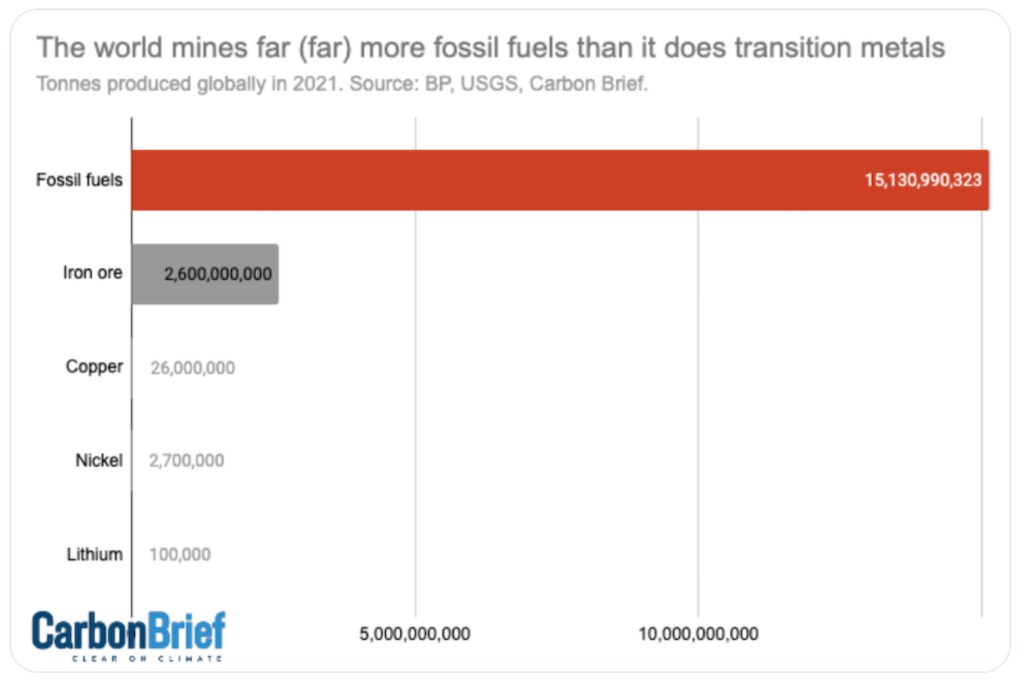

This is another category error that unfortunately Fressoz seems happy to go along with. The quantities of minerals required is minuscule compared with the huge tonnage of fossil fuels that has powered our carbon economy, as CarbonBrief illustrated as follows, as part of a debunking of 21 myths about Electric Vehicles [6]:

This false equivalence between minerals extraction and fossil fuels extraction is now widely shared by those who prefer memes to numbers.

A detailed published analysis of the demands for minerals required to build out renewables infrastructure by mid century shows we have enough to do this, without assuming high levels of recycling [7]:

“Our estimates of future power sector generation material requirements across a wide range of climate-energy scenarios highlight the need for greatly expanded production of certain commodities. However, we find that geological reserves should suffice to meet anticipated needs, and we also project climate impacts associated with the extraction and processing of these commodities to be marginal.”

Yet many commentators claim we are in danger of running out of ‘rare earths’ (which they conflate with minerals in general).

Beyond that, it is true that for many minerals it is cheaper to mine them rather than recycle them but Fressoz claims (p.218) “recycling will be difficult if not impossible”. There is no scientific basis for that claim. By 2050, one can expect that better design, improved technologies, economic incentives, and global coordination will become widely effective in tilting the balance to recycling rather than fresh extraction (and energy inputs to do this will not be an issue, as noted earlier).

And once you have built a wind farm it will continue to provide energy powered by the wind for a few decades (which is powered by the sun), without the need for material extraction or material inputs, and the faster this is done, the cheaper it gets, saving trillions of dollars [8].

A renewables circular economy is perfectly feasible, following the initial build out of the new infrastructure by mid century, with abundant energy from the sun powering the recycling needed to maintain and refresh that infrastructure.

Intermittency and grid stability

It is sad that Fressoz decides to play the it-doesn’t-always-shine card when he writes (p. 212):

“At the 2023 COP, the Chinese envoy explained that it was ‘unrealistic’ to completely eliminate fossil fuels which are used to maintain grid stability”.

… as though that settled the argument. They may have said this for UNFCCC (UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) negotiating reasons, but it is frankly pretty depressing that Fressoz shared this quote as though it reflected current informed opinion on power systems.

Firstly, even fossil fuelled generation in the early 20th Century needed flywheels to level out energy supply, and in so doing, maintain grid frequency. Such devices can live on in a renewables dominated grid. More likely is the emergence of ‘grid forming inverter’ technology that can replace inertial forms of frequency response such as flywheels and turbines.

Secondly, there are several other ways in which a grid that is 100% based on renewables can remain stable, including what is called ‘flexibility’ (including demand shifting), and distributed energy storage.

The UK is rolling out a lot of battery storage, and these have the benefit of being able to be both large and small to support the network at local, regional and national levels. Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) technology is already making an impact in the UK, Australia and elsewhere [9] demonstrating the resilience that can be achieved in a well designed and well managed grid:

“Recently, a major interconnector trip sent the UK’s grid frequency plummeting. At around 8:47am on a morning in early October [2024], the NSL [North Sea Link] interconnector linking the UK and Norway, suddenly and with no warning, halted … with immediate and potentially disastrous impact on the UK’s electricity grid … battery energy storage systems (BESS) answered the call. Across NESO’s network [National Systems Energy Operator], 1.5GW of BESS assets came online to inject power into the system, bringing frequency to strong levels within two minutes.”

Far from renewables infrastructure causing a blackout, it prevented it. Other countries can learn from this (side eye to Spain!).

A near 100% renewables grid is well within the reach of countries like Australia, and others are not far behind [10]

As the infrastructure scales up, additional storage will be added, to deal with rare extended periods of poor sunlight and low wind. The Royal Society has provided recommendations [11] on how to handle such extreme episodes.

The Primary Energy Fallacy & Electrification

While Fressoz does talk about the efficiency arising from new forms of production and consumption, he does not really chose to provide any numbers (which is in stark contrast to the slew of numbers he uses when talking about wood, coal, oil, etc.).

He then makes the point (p. 214):

“In any case, electricity production accounts for only 40 per cent of emissions, and 40 per cent of this electricity is already decarbonised thanks to renewables and nuclear power.”

He channels arguments that readers of Vaclav Smil will be familiar with. Telling us how hard it will be to decarbonise steel, fertiliser production, flying, etc.; no solutions, sorry.

Even S-curves (that show how old technology is replaced by new) are disallowed in Fressoz’s narrative, because they are too optimistic, apparently, even though there is empirical evidence for their existence [12].

Just a ‘too hard’ message.

What he fails to mention is that the energy losses from using fossil fuels are so large that in electrifying the economy, we will need only about one third of primary energy hitherto needed (using renewables and nuclear). So, in the UK, if we needed 2,400 TWh (Terawatthours) of primary energy from fossil fuels, in an electrified economy powered by renewables, we’d only need 800 TWh to do the same tasks.

The efficiencies come both from power production, but also from end use efficiencies, notably transportation and heating. By moving to electric vehicles (trains, buses, cars) and heat pumps, we require only one third of the energy that has hitherto been used (from extracted coal, oil and gas). This is massive and transformational, not some minor efficiency improvement that can be shrugged off, as Fressoz does,

Green production of steel, cement and fertiliser is possible and in some cases already underway, although currently more expensive. Progress is being made, while flying is more difficult to crack. Together these sectors account for about a quarter of global emissions. Yet, road transport and heating together also represent about quarter of global emissions [13], and are easy to decarbonise, so I guess don’t fit into the book’s narrative.

The surprise for many, who are effectively in thrall to the primary energy fallacy, is that we can raise up the development of those in need while not necessarily increasing the total energy footprint of humanity. We can do more and more, with less!

Who is deluded?

In his essay The Delusion of “No Energy Transition”: And How Renewables Can End Endless Energy Extraction, Nafeez M Ahmed offers an eloquent critique of Fressoz’s book [14].

A key observation Ahmed makes is that Fressoz’s use of aggregate numbers masks regional variations in a misleading way:

“Because he fails to acknowledge the implications of the fact that this growth is not uniform across the globe at all, but is concentrated in specific regions. The aggregate figures thus mask the real absolute declines in wood fuel use in some regions as compared to the rise in others. Which means that oil and wood fuel growth are not symbiotically entwined at all.”

Ahmed goes on to present the arguments about the different nature of the move to renewables, electrification of end-use and so on, in an eloquent and persuasive way. I strongly recommend it.

Fressoz is right to claim that many have been seduced by a simplistic story about past transitions. His book is very entertaining in puncturing these delusions, but he overplays his hand. Ahmed argues convincingly that Fressoz has failed to demonstrate that his methods and arguments apply to the current transition.

Fressoz’s attempt to conjure up a new wave of symbiosis fails because he misunderstands and misrepresents the fundamentally different nature of renewables.

Is there a case for degrowth?

Of course, we do live in a world of over consumption and massive disparities in wealth (and over consumption does not seem to be a guarantee of happiness).

The famous Oxfam paper on Extreme Carbon Inequality from 2015 [15] showed how the top 10% of the world (in terms of income) were responsible for 50% of emissions, and the bottom 50% were responsible for 10% of emissions. An obscene asymmetry. As Kate Raworth argues in Doughnut Economics, we need to lift up those in need, while reducing the overconsumption of some that threaten planetary boundaries.

Yet we do not help those in poor countries by getting them hooked on fossil fuels. Indeed, renewables offer the opportunity to avoid the path taken by the so called ‘developed world’, and go straight to community-based renewable energy. This can be done – at least initially – without necessarily needing to build out a sophisticated grid: solar, wind, storage and electrified transport, heating and cooking is a transformative combination in any situation. We can increase the energy footprint of the poorest (providing them with the development they need), while reducing their carbon footprint.

Yet many want to play the zero sum game. True, there is a carbon budget (to remain below some notional global target rise in mean surface temperature, we cannot burn more than a quantity of carbon; the budget). We should share it out this dwindling budget fairly, but honestly, will we?

The game is nullified if people simply stop burning the stuff! The sun’s energy is functionally infinite (in any meaningful timeframe), so why not reframe the challenge? How about the poorest not waiting for, or relying on, the ‘haves’ suddenly getting a conscience and meeting their latest COP (Conference Of the Parties) promises? Countries like Kenya are already taking the lead [16].

Energy Independence and Resilience within our grasp

There are of course multiple interlocking crises (climate, nature, migration, water, and more). They are hard enough to deal with without claiming that energy should join them.

The land use needed for our energy needs is small compared to what is needed for agriculture and nature, so again, renewable energy is not part of another fictitious zero sum game involving land use.

A paper from the Smith School in Oxford [17] has found that wind and solar power could significantly exceed Britain’s energy needs. They found that even if one almost doubled the standard estimates of the energy needs (to cater for new demands such as circular economy, AI and synthetic meat in 2050), there were no issues with the area of land (or sea) required:

- Solar PV 4% of British Rooftop

- Solar PV 1% of British Land*

- Wind Onshore 2.5% of British Land

- Wind Floating Offshore 4% of UK’s exclusive economic zone.

… and bearing in mind that 30% of land is currently used for grazing.

The scare stories about prime arable land being covered in a sea of solar panels is politically motivated nonsense.

I gave a talk Greening Our Energy: How Soon, on how to understand how the UK has made the remarkable transition from a fossil fuel dominated energy sector to our current increasingly decarbonised grid, and how the journey will look going forward (and in a way that is accessible to lay people) [18].

In a world of petrostates and wars involving petrostates, there has indeed been repeated energy crises, and they will get worse while we remain addicted to fossil fuels.

Transitioning to a green energy future is the way out. It is already under way, we have the solutions. We just need to scale them up, and ignore the shills and naysayers.

Let’s not say or imply that solving the many injustices in the world is a pre-condition to addressing the energy transition. This is the false dilemma that is often presented in one form or another, often from surprising quarters, including ostensibly green ones. It is a prescription for delay or inaction.

Achieving green energy independence and resilience might actually undermine the roots of many of those power structures that drive injustices, because energy underpins so much of what communities need: education, health, food, and more.

John Lennon seems to says it right in his song “Power to the people”.

© Richard W. Erskine, 25th June 2025

References

- More and More and More – An All-Consuming History of Energy, Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, Allen Lane, 3rd October 2024

- Historian Jean-Baptiste Fressoz: ‘Forget the energy transition: there never was one and there never will be one’, By Bart Grugeon Plana, Jorrit Smit, originally published by Resilience.org, December 2024, https://www.resilience.org/stories/2024-12-05/historian-jean-baptiste-fressoz-forget-the-energy-transition-there-never-was-one-and-there-never-will-be-one

- Future of Earth, wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Future_of_Earth

- Energy: Engine of Evolution, Frank Niele, Shell Global Solutions, 2005

- The Fallacy of Perfection, Richard Erskine, essaysconcerning.com, 4th April 2024, https://essaysconcerning.com/2024/04/04/the-fallacy-of-perfection/

- Factcheck: 21 misleading myths about electric vehicles, Simon Evans CarbonBrief, 24th October 2023, https://www.carbonbrief.org/factcheck-21-misleading-myths-about-electric-vehicles/

- Future demand for electricity generation materials under different climate mitigation scenarios, Seaver Wang et al, Joule, Volume 7, Issue 2, 15 February 2023, Pages 309-332. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2542435123000016

- Decarbonising the energy system by 2050 could save trillions – Oxford study, https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2022-09-14-decarbonising-energy-system-2050-could-save-trillions-oxford-study

- The role of BESS in keeping the lights on, Kit Million Ross, Solar Power Portal, 30th October 2024. https://www.solarpowerportal.co.uk/the-role-of-bess-in-keeping-the-lights-on/

- A near 100 per cent renewables grid is well within reach, and with little storage, David Osmond, Aug 24, 2022, https://reneweconomy.com.au/a-near-100-per-cent-renewables-grid-is-well-within-reach-and-with-little-storage/#google_vignette

- Large-scale electricity storage, Royal Society, September 2023. https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/large-scale-electricity-storage/large-scale-electricity-storage-policy-briefing.pdf

- One in three UK car sales may be fully electric by end ‘23 as S-Curve transforms market, Ben Scott and Harry Benham, CarbonTracker, 5th January 2023. https://carbontracker.org/one-in-three-uk-car-sales-may-be-fully-electric-by-end-23-as-s-curve-transforms-market/

- Cars, planes, trains: where do CO₂ emissions from transport come from?, Our World In Data, https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions-from-transport (Our World In Data provides data on other sectors too).

- The Delusion of “No Energy Transition”: And How Renewables Can End Endless Energy Extraction, Nafeez M Ahmed, Age of Transformation, 24th April 2025, https://ageoftransformation.org/the-delusion-of-no-energy-transition-and-how-renewables-can-end-endless-energy-extraction/

- Extreme Carbon Inequality, OXFAM, 2015 https://www.oxfam.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/mb-extreme-carbon-inequality-021215-en-UPDATED.pdf

- Doing development differently: How Kenya is rapidly emerging as Africa’s renewable energy superpower, Rapid Transition Alliance, 1 November 2022. https://rapidtransition.org/stories/doing-development-differently-how-kenya-is-rapidly-emerging-as-africas-renewable-energy-superpower/

- Wind and solar power could significantly exceed Britain’s energy needs, Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, Oxford University, https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2023-09-26-wind-and-solar-power-could-significantly-exceed-britain-s-energy-needs

- Greening Our Energy: How Soon? Looking back and looking forward, to 2030 and beyond – A layperson’s guide, Richard Erskine, essays concerning.com, https://essaysconcerning.com/2024/12/21/greening-our-energy-how-soon-looking-back-and-looking-forward-to-2030-and-beyond-a-laypersons-guide/

Thank you Richard – indeed to all of that. Lennon got a lot right; he could have perhaps suggested ‘led by the people’. The clarity that Elinor Ostrom brought to the issue of local resources (being best managed by local interests) is just another take on Schumacher. The big give away on Net Zero racketeering is that any of us should be paying any more for this – the reverse sould be true. Evident mismanagement and corruption in the Water Industry is just one of many illuminations of how we are all being ‘robbed rotten’.

LikeLike

Thank you Julian. The concept of abundance must terrify those that gain so much from trading on scarcity.

LikeLike