Most people have heard about chaos theory, especially as it applies to weather, but may be a little fuzzy about what it all means. They may even hear people claim “if they can’t even predict the weather in a month’s time, how on earth can they tell us what the climate will be in 25 years time?!”.

It’s a fair challenge, but one that has been answered many times by climate scientists [1], but often in ways that perhaps are not as accessible as I feel they could be. When I was recently asked this question I was frustrated I could not share a plain English article with them.

So here is my attempt in plain, non-scientific language to explain how we can project future climate, despite ‘chaos’. I will use the analogy of rolling dice to help explain things – so no equations or mathematical jargon, I promise.

Chaotic Weather

Let’s start with the discovery of ‘chaos’ by Lorenz in 1963 [2]. Weather projections have to start from the current state of the weather and then project forward. The models incrementally step forward to see how the weather patterns evolve over minutes, hours and days. Lorenz discovered that even with the simplest models, if one did two ‘runs’ of the model which had an infinitesimal difference in initial conditions (eg. the temperature in Swindon at 15.0oC and 15.00001oC) the predicted weather can look very different in just a few weeks..

If this was just a trivial observation that errors can magnify themselves in a complex system, one might be tempted to shrug one’s shoulder – and it was not even a new insight [3]. But Lorenz discovered something far more profound: beautiful patterns amongst the chaotic behaviour of complex systems (think of the eddy currents that appear in the turbulent flow of a river). For those interested in learning more about Lorenz’s mathematical legacy, Professor Tim Palmer gave an interesting talk on this [4].

I say ‘errors can magnify’ because sometimes you end up with a chaotic outcome and sometimes you don’t [5]. This is important if you are about to head off to Cornwall for your summer holiday. Weather forecasters now do multiple runs of the models varying the initial parameters [6]. If all the outcomes look similar then the weather system is not behaving chaotically – at least over Cornwall for the period of interest – and the weatherman can say confidently “it will be dry next week over Cornwall”. If, however, out of 100 runs, 20 indicate wet and windy weather, and the rest were dry, they’d say “There is a good chance of dry weather over Cornwall next week, but there is a 20% chance of wet and windy weather”, so take your waterproofs!

Predictable Climate

It really is all about the question being asked, as with most issues in the world. If you ask the wrong question, don’t be surprised if you get a misleading answer.

If I ask the question “will it be sunny in Cornwall on the 3rd of July of 2050?” (wrong question) then it is impossible to say, because of ‘chaos’. If, on the other hand, I ask the question “do we expect the average temperature over Cornwall to be higher in the summer of 2050 as a result of our carbon emissions compared to what it would have been without those emissions?” (longer but valid question) I can answer that question with confidence; it is “Yes”.

This illustrates that when we talk about weather we are interested, as in our holiday plans or a farmer harvesting their crops, in the specific conditions at a specific place and specific time.

Climate is very different, because it is about the averaged conditions over a longer period and typically wider area.

Throwing the dice

I want to illustrate the difference between these two types of question (specific versus averaged) by use of a dice [7] analogy.

If I throw a dice I expect that the chance of getting a 6 to be 1 in 6. If I ask the (specific) question ‘what will the hundredth throw of the dice show?’ (think weather), I am no more certain of the outcome than after 10 throws [8].

Now ask a different question: ‘what will be the average number of 6s after 600 throw?’ (think climate). I would expect it to be around about 100. As the number of throws increases I’d expect the average (number of 6s divided by the number of throws) to get closer and closer to 1 in 6.

This is just how statistics comes to the rescue in the face of the much used, and abused, “chaos” in the climate debate.

You can do this yourself. Make multiple throws of a dice, and after each throw, take the count of the number of 6s thrown and divide by the number of throws – that is the observed odds. You might be surprised to find how long it takes before the odds settles down to close to 1 in 6.

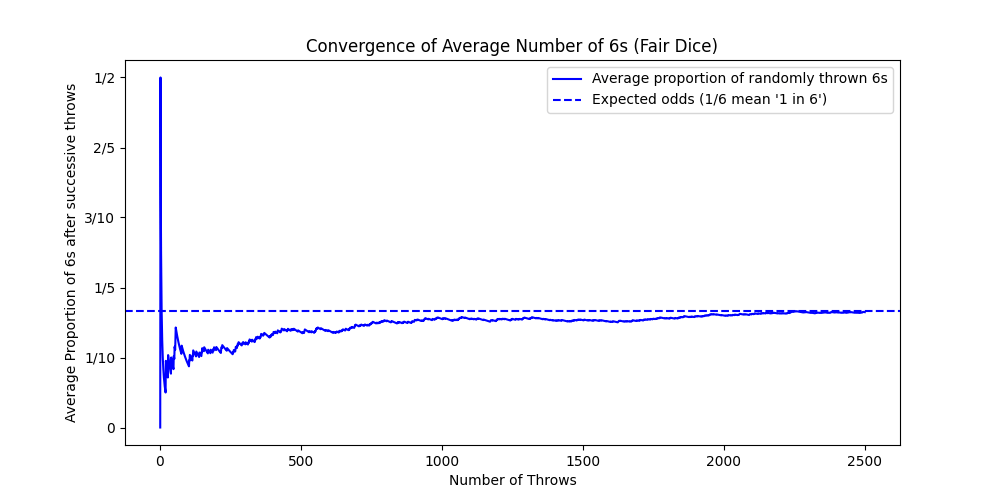

Being lazy, I wrote a little program to plot the result (using a random number generator to do the ‘throwing’ for me).

The averaged number of 6s converges on the expected odds of 1/6 (shorthand for ‘1 in 6’).

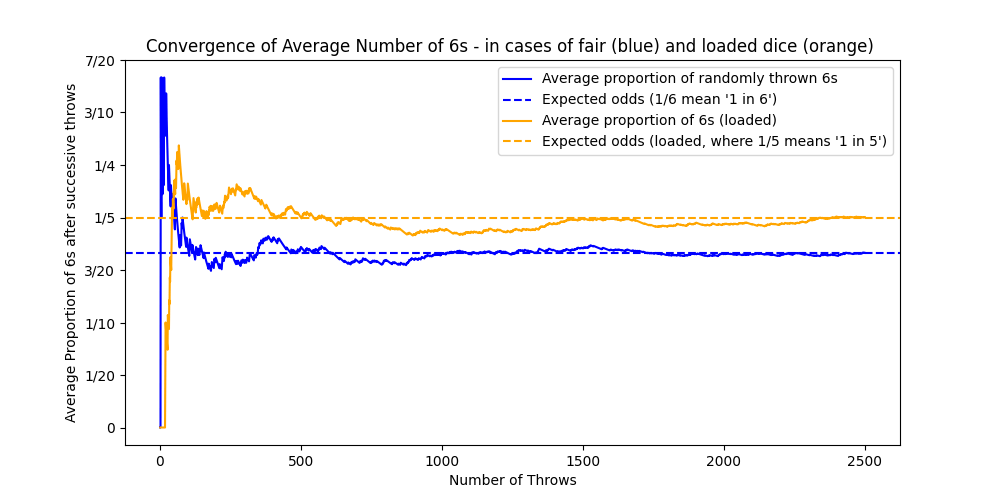

I then imagined two dice, one that was ‘fair’ (where the odds of throwing a 6 were 1 in 6) and a ‘loaded’ dice (where the odds have changed to 1 in 5). This is a analogy for a changed climate where carbon emissions have been happening for some time but have now stopped, and there is a raised but stable concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. This gives rise to a higher averaged temperature, represented by the higher odds of throwing a 6 in this analogy (see next illustration).

Despite the uncertainty in any specific throw (think weather) in both cases, the average chance of getting a 6 can be predicted (think climate) in both cases. We can see the loaded dice clearly in the graph, compared to the fair dice. In both cases it takes a little time for the influence of randomness (chaos if you like) to fade away as the number of throws increases.

However, the emissions have not stopped, and in fact have been growing since the start of the industrial revolution. There has been a significant acceleration in emissions in the last 75 years. So the amount of accumulated greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has been growing, and with it, the averaged surface temperature on Earth.

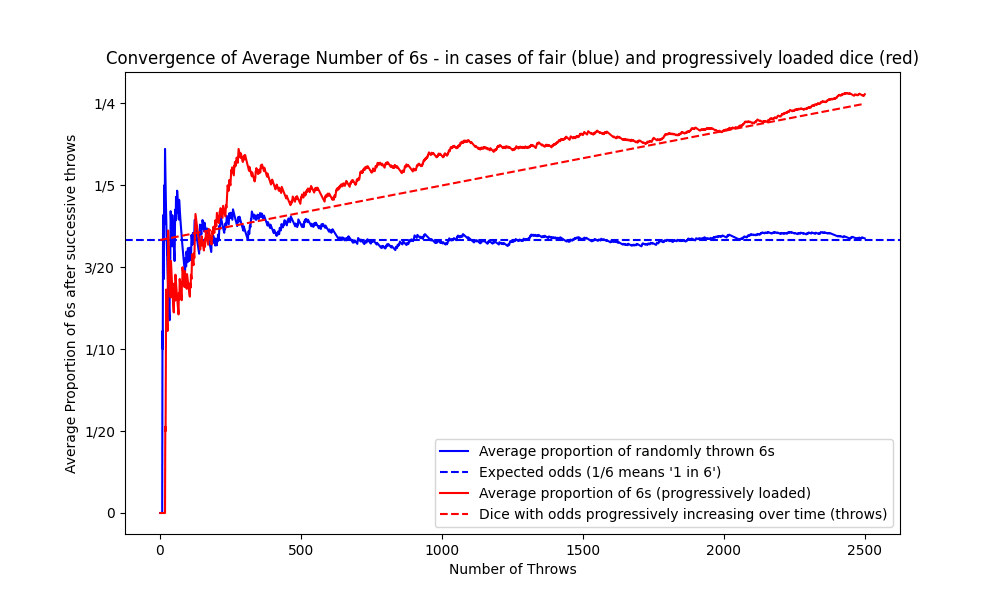

So, taking the analogy one step further, I created a dice that gets progressively more ‘loaded’ over time (think each year of emissions).

Now, the averaged chance of throwing a 6 will progressively increase, compared to the fair dice. This is illustrated in the next graphic.

Again, we see the averaged odds after a number of throws jump around for quite a while (think chaos), but things settle down after a several hundred throws.

We now see a clear and ever widening gap between the two dice.

This is analogous to what is happening with our climate: our continuing carbon emissions are progressively loading the ‘climate dice’.

No amount of weather chaos can cancel the climate statistics that become more evident with every year that passes.

Extreme Weather Events

Now while weather and climate are different, because climate is an average of what the weather is over time, there is an interesting flip-side to this. Since the climate changes due to our carbon emissions, that means the spread of possible weather must have also shifted, to generate a new average.

This means that extreme weather events become much more likely.

Once again, this is just basic statistics. So events that may have been “one in a hundred years” become much more frequent, and very extreme events, like the 40oC we saw in England in 2022, that were “basically impossible” without our carbon emissions [9], now start to happen.

I don’t want to make this essay longer explaining how this works, and the Royal Statistical Society have done a great job on this, so please visit their explainer [10].

Extreme weather events are now popping up all over the world, almost on a weekly basis, and thanks to the statistics and associated modelling, scientists can now put a number on how much more likely each event has become due to our carbon emissions [11].

We have already loaded the climate dice, the question now is, how much more do we want to load it, and make the odds even worse?

© Richard W. Erskine, September 2025

Notes

- Chaos and Climate, James Annan and William Connolley, RealClimate, 4th Nov 2005.https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2005/11/chaos-and-climate/

- Edward Lorenz, Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow, Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 20 (2): 130–141, https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/atsc/20/2/1520-0469_1963_020_0130_dnf_2_0_co_2.xml

- Stephen Wolfram wrote some historical notes on chaos theory https://www.wolframscience.com/reference/notes/971c/

- The Butterfly Effect – What Does It Really Signify, Tim Palmer, Oxford Mathematics, 19th May 2017, https://youtu.be/vkQEqXAz44I?si=bLBWR7hLNsHBaE5E

- Over the specific place and time period of interest, of course.

- This is called ‘ensemble modelling’.

- For the grammar police: common usage now prefers ‘dice’ for singular and plural cases.

- In this sense, the dice analogy is somewhat different to climate, because climate change is conditional on what came before, but this does not change the point of the analogy – to distinguish between specific and averaged questions.

- UK’s 40oC heatwave ‘basically impossible’ without climate change, Georgina Rannard, 29th July 2022, BBC, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-62335975

- Explainer: Extreme Weather, Royal Statistical Society, https://rss.org.uk/policy-campaigns/policy/climate-change-resources/explainer-extreme-weather

- World Weather Attribution, https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/