If people are confused about what to do about climate change in their everyday lives, they have every right to be.

Fossil fuel companies have for decades funded disinformation through a network of ‘think tanks’, and commentators, planting stories in the media. This was all helped by PR and Advertising agencies who know how to play with people’s emotions; to create fear, uncertainty and doubt.

Many have explored this issue more deeply than I ever can or will. Notably, Oreskes and Conway showed, in their book Merchants Of Doubt [1], how the same tactics used to promote smoking and deny its harms, were used by tobacco companies.

We might imagine we can now see through their tactics. I’m not so sure. I feel there is a tendency amongst some progressives to almost fall into the trap of amplifying the messages.

I am thinking of how some who claim that heat pumps are for the comfortably well off and it’s not fair to push them for those in energy poverty. The alternative – to stick with the comfort zone of insulating homes – came to be the default. This is not fair to anyone.

Before we get on to that, let’s start with the birth of ‘climate shaming’.

Climate Shaming 1.0: It’s your demand that’s the problem!

It is well established that fossil fuel companies like Exxon and their network decided to make you, the consumer, the problem [2].

The message:

It’s you driving your car and running your gas boiler. We are just meeting your demand, so don’t blame us.

Intended result:

Guilt, denial and inaction.

It is even alleged that BP and their communication agency Ogilvy cooked up the idea of ‘carbon footprint’ [3]. We could all then measure our level of guilt. No wonder people often resorted to tiny actions to salve that guilt, when they felt powerless to do more.

Yet, there is a counter argument that while this was and remains a key plank in the strategy to delay action, measuring things can be useful. What is needed is to shake off the guilt and find ways to act.

Climate Shaming 2.0: It’s all your fault!

Shaming has metastasised into everything we do that we can feel guilty about, where fossil fuels are often out of sight.

There are many voices at work here, but in the background, fossil fuel interests are keen to keep the heat on you, dear citizen, rather than them.

They will claim to be doing their bit, with greenwashing PR and advertising … now over to you people!

While they don’t control every part of this conversation we have amongst themselves, they have the wherewithal to influence it in a myriad of ways. The message we receive is, “don’t do this bad thing” (but we, fossil fuel interests, won’t help you):

Don’t fly to Europe (but we won’t divert fossil fuel investments into trains)

Don’t eat meat (but we’re happy to reinforce your guilt, when the Amazon burns; for cattle feed)

Don’t eat Ultra Processed Foods (but like this behemoth, we work hard to ensure law makers give our fossil fuel interests a free pass)

Feeling guilty? Feeling helpless?

(laughing emoji from fossil fuel boardrooms)

Recognising our agency

We are told by some progressive politicians and commentators that it’s all about system change, and that we should reject the idea that it is our fault. We can’t take an EV Bus if there is a bad bus service (and they are still run on diesel), we need to invest in rural public transport not just in the cities.

There is a lot of truth in this, but it isn’t quite that simple.

We are not separate from the system, and it is hardly ‘systems thinking’ to imagine such a separation. The system includes Government, business, civic society and the natural environment, interacting in numerous ways.

Citizen-consumers have a lot of identities (community members, consumers, voters, parents, volunteers, etc). These identities each have their own form of agency, which we can choose to use. We need the spirit of positive change in the choices we make:

To choose who to vote for.

To chose where we spend our money.

To choose where to go on holiday and how to get there (and if/how often to fly).

To modify our diet (reducing meat if not eliminating it).

To decide to buy quality clothing that is repairable (looking and feeling better).

To decide where we bank and where we invest through our pensions.

Even when an action one would like to take (like getting an EV) is not yet in reach, one can keep exploring options and set a goal for when it does come within reach.

Setting goals too is an achievement.

The shaming tactic of the fossil fuel interests is aimed at breaking our sense of agency. We have to organise and support each other and reclaim our agency, as individuals and as communities.

The Take The Jump initiative [4] espouses practical steps we can take, while recognising we also need system change.

Electrification of energy end-use is a key threat to fossil fuel interests

There are a range of solutions available now to make a serious dent in our carbon emissions. The most significant and relatively easy thing to achieve is to electrify our primary energy and energy consumption. These solutions are so brilliant they have become a threat to fossil fuel interests, notably:

- Electric Vehicles (EVs) of all kinds will not only clean up our towns and cities but are so much more efficient than their fossil fuel alternatives. They require only a third of the energy of a petrol/ diesel car to run them.

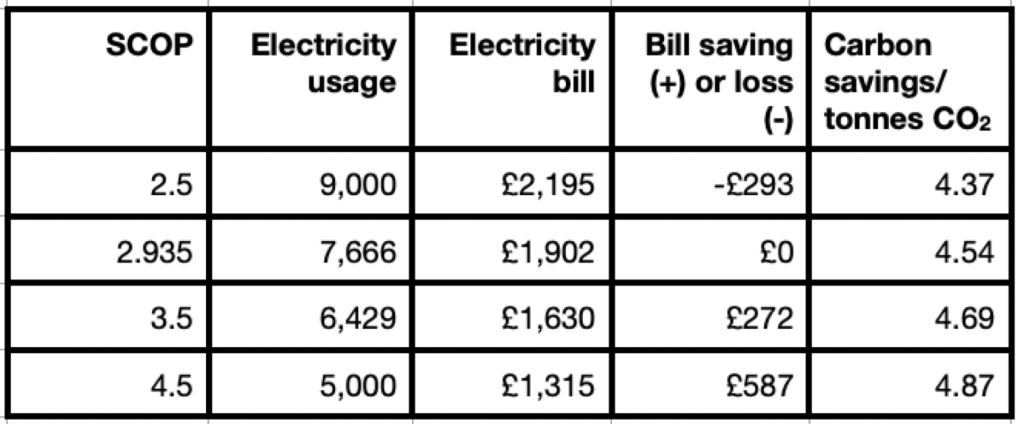

- Heat Pumps are so much more efficient than their fossil fuel alternatives. They require between a third and a fifth of the energy needed to run a gas boiler.

- Both EVs and Heat Pumps are powered by electricity. When generated by solar and wind, it is both free and unlimited, because it is derived from the Sun (which deposits 10,000 times as much energy on Earth as humanity is ever likely to need).

There has been an incessant effort by the network of fossil fuel interests to plant stories and create memes aimed at trying to undermine this transition to clean, electrified energy use.

They know they will eventually lose, because the science of thermodynamics and economic reality mean it’s inevitable. Yet they will try to delay the transition for as long as possible. They can then extract as much fossil fuels as they can, and avoid ‘stranded assets’. Whereas, if they truly cared about climate change they would be working to leave it in the ground.

This essay is not the place to enumerate every myth and piece of disinformation that relentlessly circulates on social media about EVs and Heat Pumps. Carbon Brief have done the myth busting for you [5].

Climate Shaming 3.0: It’s ok for you woke well-to-do!

In order to counter this threat a new form of shaming emerged, particularly in relation to personal choice. I’m calling it Climate Shaming 3.0.

If one believed the framing so often evident in right-wing papers like the Mail and Telegraph titles, EVs and Heat Pumps are (paraphrasing)

… for the woke well-to-do – something they can afford but is not any good for most people …

If it was only these usual suspects one might try to shrug off this chatter.

Unfortunately, there has emerged an unholy alliance amongst those who would regard themselves as green progressives (in a non political sense), who are in a way doing exactly what the fossil fuel messaging is intended to promote.

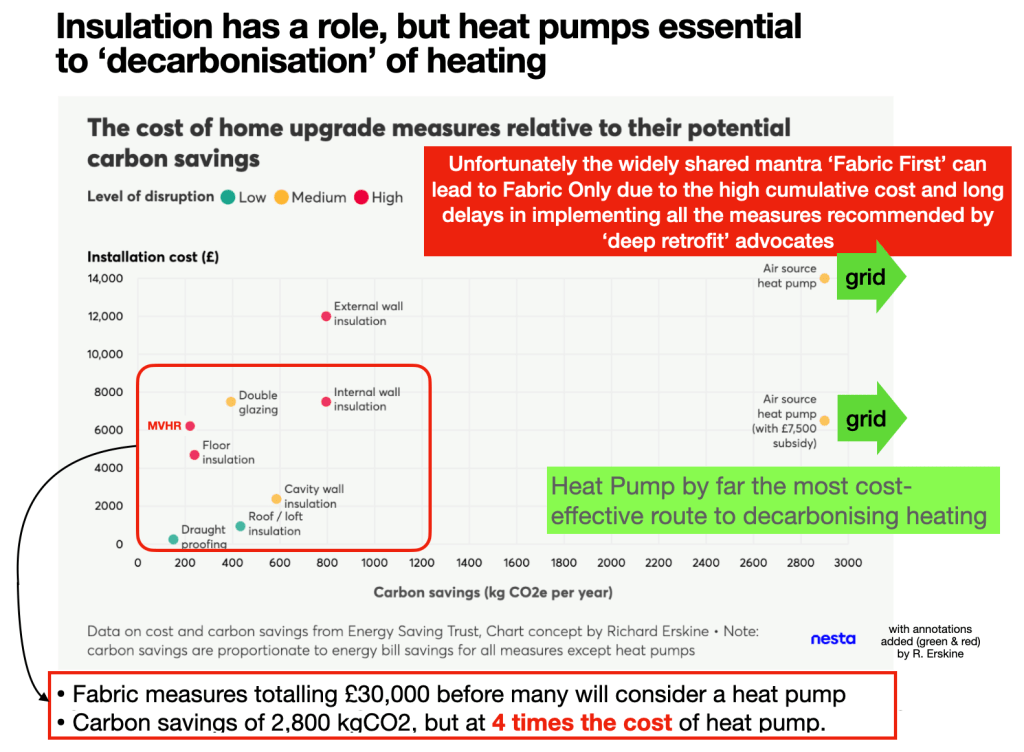

We have politicians of all kinds who have been cowed by toxic reporting on heat pumps who – wanting to show they are addressing fuel poverty – will talk endlessly about the need to insulate homes. Yet they dare not use the words ‘heat pump’ for fear of being accused of elitism (even though a heat pump is a far more cost-effective route to decarbonising heating than deep retrofit [6]).

They must be laughing their heads off in the boardrooms of fossil fuel companies.

Is it really ‘climate justice’ to promote the poorly designed ECO (Energy Company Obligation) scheme that the NAO (National Audit Office) declared [7] has been a total failure? NAO found that external wall insulation, for example, has led to bad and often exceptionally bad outcomes 98% of the time. This has required very expensive re-work in many cases, compounding the injustice.

This is to be contrasted with the BUS (Boiler Upgrade Scheme) that – despite all the claims about a lack of skills in the sector – has helped to really pump prime the heat pump sector and can be regarded as a success.

Communities like Heat Geek are really shaking things up too, to lower installation costs and improve the quality of installations (to the level already practiced by many small businesses with great track records).

The unholy alliance extends to plumbers, retrofit organisations, council officers, architects and politicians who claim you cannot heat an old building without deep retrofit. A disproven and false claim, but repeated as many times as the story about British pilots seeing better in WWII thanks to eating carrots.

Some untruths live on through repetition.

The idea that we can insulate our way out of energy poverty, without also pushing at least as hard on rolling out heat pumps (individually or using shared heat networks) is an illusion, that would mean we’d be stuck with burning gas for much longer than necessary.

More laughter from those boardrooms.

Insulation, replacing windows and other fabric measures are important but you can easily blow so much money on these that you leave nothing in the pot for a heat pump [6].

Here is a diagram from Nesta that was based on one I originally produced and here I have added some further annotations (see [6] for Nesta version):

That is not climate justice, or fair on anyone.

It is not climate justice for those in energy poverty to have to pay for gas that will inevitably go through repeated market crises and cost spikes in its dying decades.

Climate justice is future proofing our electricity supply, the grid, our homes and our streets.

These will then be not only cleaner and more efficient but future proofed. As the late Professor Mackay observed, once you have electrified end use of energy, the electricity can come from anywhere: from your roof, from a community energy project, or from a wind farm in the north sea.

It’s time that those that claim to be progressives stopped falling for the tactics of fossil fuel interests, that time and again are slowing our transition to a clean energy future, and action on climate change.

It started with shaming people for their consumption. Let’s not fall for the new tactic of shaming those who actually care enough to adopt effective solutions.

References

[1] Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, 2010, Bloomberg Press.

[2] Exxon Mobil’s Messaging Shifted Blame for Warming to Consumers, Maxine Joselow & E&E News, Scientific American, 15th May 2021.

[3] Can fossil fuel companies really support a carbon tax?, Alain Naef, SUERF Policy Brief, No 724, November 2023.

[4] Take The Jump, https://takethejump.org/

[5] Carbon Brief

- 18 Misleading Myths about Heat Pumps, https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/factcheck/heatpumps/index.html

- 21 Misleading Myths about EVs, https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/factcheck/electric-vehicles/index.html

[6] ‘Insulation impact: how much do UK houses really need?, NESTA, 8th January 2024, https://www.nesta.org.uk/report/insulation-impact-how-much-do-uk-houses-really-need

[7] Energy efficiency installations under the Energy Company Obligation, 14th October 2025, National Audit Office https://www.nao.org.uk/reports/energy-efficiency-installations-under-the-energy-company-obligation/